This past week the Columbus Symphony with Music Director Rossen Milanov performed Shostakovich 10 and the Britten Violin Concerto featuring our Concertmaster Joanna Frankel. For this demanding concert I found that in order to do justice to each solo and exposed passage, I had to use no less than 4 different reeds. Furthermore, some of those reeds were used

more than once during each concert. That's a lot of reed juggling, and it goes against my usual policy of playing the entire concert on one reed to avoid the distraction of fussing with equipment.

Why did I decide to put myself through the hassle of keeping track of 4 alternating reeds? This past week I couldn't ignore the vast differences in sound and character among my various reeds. The program featured the bassoon over and over in a wide variety of exposed passages and I decided that in order to really sound my best on each of those passages, reed changes would be necessary. Certainly I could have used one reed for everything, but the result would have been a compromise to say the least.

The last time I played Shostakovich 10 I wrote about it on this blog. Apparently I didn't fuss quite as much with reeds back then. We musicians are constantly raising our standards and expecting more of ourselves, so it makes sense that I'm more particular about reeds than I used to be.

Does that mean I'm recommending using multiple reeds for a concert? Not necessarily - it depends upon how much of a difference it seems to make, and whether or not your concentration is reliable enough to successfully execute the reed changes. During Friday night's concert, my concentration proved to be fallible. I missed an exposed entrance in the Britten Violin Concerto due to nearly forgetting a reed switch (and executing it later than planned) thereby demonstrating why I normally prefer not to switch reeds. As one might imagine, I had carefully marked all the reed changes in my parts (using numbers to identify the different reeds) but sometimes it's possible to accidentally overlook even the most clearly marked instructions.

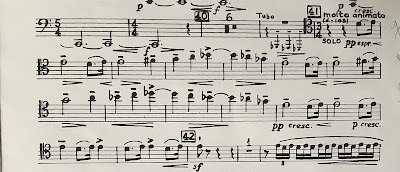

In many professional orchestras there is an assistant, associate or co-principal bassoon. That person would most likely play the Britten Violin Concerto on a program such as this one. In Columbus the principal woodwinds play everything - there are no assistants. Playing the Shostakovich is daunting enough, but it turns out that the Britten is no stroll through the park either! There is a solo near the end of the Britten which, under different circumstances, would give pause:

|

| yellow squishy earplug lodged under low C key (to de-activate the low note keys) |

|

| This is conducted in one beat per measure, so the 8th notes are fairly fast. Also, this is a passage that benefits from paying close attention to the conductor. |

|

| Movement IV solo |

|

| Exposed passage in octaves with contrabassoon near the end of movement I |

|

| from movement II |

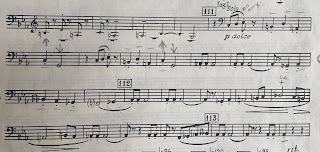

The bassoon solo in the third movement would normally be a fairly big deal for an instrument which is so often neglected by composers! In this particular symphony, however, it is quite overshadowed by more dramatic solos. Still, I struggled with finding the right reed for this:

|

| Third movement solo |

I tried many different reeds for this, but it never sounded quite right. Our concert hall is extremely dry and I thought this solo needed some resonance to sound decent. Finally, by the last concert I found a reed that I was more satisfied with. It was the same reed that I used for the loud low solos. Originally I didn’t think this solo needed a low reed, but eventually my nonstop experimentation revealed that a low reed was helpful in creating the illusion of resonance.

After the major solo in the 4th movement the bassoon begins a series of low exposed passages:

|

| from the 4th movement |

This is in unison with the low strings. If you try to hear the strings (who are likely to be located quite a distance away from you) and play with what you hear, you’ll likely end up lagging behind. Instead, it’s advisable to follow the conductor. We often hear conductors telling the strings to listen back to the winds. This is one of those situations when we truly hope that happens.

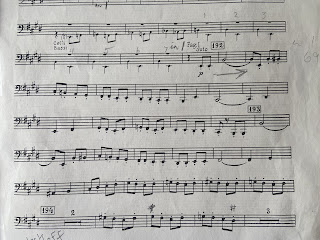

The final bassoon solo of Shostakovich 10 probably inspires a reed change for even the most laid back of bassoonists. It’s not that it can’t be played on a “normal” reed, but a reed specializing in the low range may ensure that each note responds on time, with a big sound, and perhaps most importantly, in tune. This jaunty solo presents a carefree reversal of Shostakovich’s depiction of Stalin with despair, terror and rage which had characterized the symphony until this point.

|

| Final bassoon solo of Shostakovich 10 |