I learned to make reeds when I was 14. The method I learned originally differs from my current reed making method, but I'm glad I started early. There's no doubt that it takes a ton of time and experience to learn to create a good bassoon reed.

Here are the steps I teach to young students:

Sand the inside of the dry cane until it's as smooth as glass. Use 320 grit wet and dry sandpaper. Then soak the cane in water for around 2 hours.

Next, score the bark using a knife or special scoring tool:

Next, fold the cane over a knife (at the fold line in the center) and place the end of a ruler at the fold. At 2 5/16" mark the cane with a pencil. That's the line at which you'll cut off the ends of the cane:

Next cut off each end (cutting on the line marked with pencil) with pruners:

Then fold the reed, line up the edges, and apply the top wire at exactly 1″ from the bottom of the reed. Wrap string around the reed from the top wire down:

Next, squeeze the sides of the wrapped tube with pliers or parallel pliers (very difficult to find):

Next insert the forming mandrel, being careful not to twist the reed:

Then unwrap the string at the very bottom of the reed to make room to add a wire at the bottom of the tube to ensure roundness. Wrap this wire around the tube 3 times rather than the usual 2 times.

Ideally, allow the blank to dry for at least 2 weeks. Brass mandrel tips from Christlieb are ideal for ensuring the proper shape of the tube, and they may be purchased in large quantities.

After at least 2 weeks, remove both wires from the dry blank:

Then bevel using a sanding block (made by gluing 320 grit sandpaper onto a wooden block). Each end of the cane is sanded around 25 strokes or so - whatever it takes to make the ends of the reed halves meet perfectly. The sanding takes place at the ends of the bark, from the bottom to 3/8" up:

This is the end of the reed before beveling:

And after beveling:

Then fold the reed and tie dry string around the bottom half of the tube (bark):

Apply the middle wire at 5/16' below the top wire (you will be able to see the marks where the top wire was placed):

Then apply the bottom wire at 3/16" from the bottom of the reed, and the top wire at 1" from the bottom:

Next apply Duco Cement along the edges of both sides from the middle wire

down to the bottom to prevent any future leakage or loosening of the binding:

Then wrap the reed with 100% cotton #3 size crochet thread, available at places like JoAnn Fabrics and Michael's Crafts or online from crochet suppliers:

After wrapping, cover the binding with Duco Cement and allow it to dry overnight:

Next mark the 2 1/8" line at the top of the reed:

But don't cut the tip off yet! Reaming is next, assuming that the reed needs it, followed by smoothing the inside of the tube with a rat tale file if needed.

Using a knife, cut the corners at a 45 degree angle:

Now it's time to finish and refine the reed, with a file, knife or sandpaper, removing cane in the area shaded below:

It is important to strive for symmetry. Each point on the blade has 3 corresponding points, and all 4 should be equal in thickness.

My finished reeds measure 2 1/8″ from top to bottom. The blade is 1 1/16″ long from the top of the collar to the tip, and the collar measures 1/16″. The bottom wire is 3/16″ from the bottom of the tube. The top wire is 1″ from the bottom, and the middle wire is 5/16″ below the top wire. Occasionally I experiment with different dimensions if a student has cane which is clearly intended to produce a larger reed. (My reeds are on the small side.)

Good luck, and don't give up no matter what transpires! Remember that a bassoon reed is really a much-fussed-over vegetable.

| ||||||||

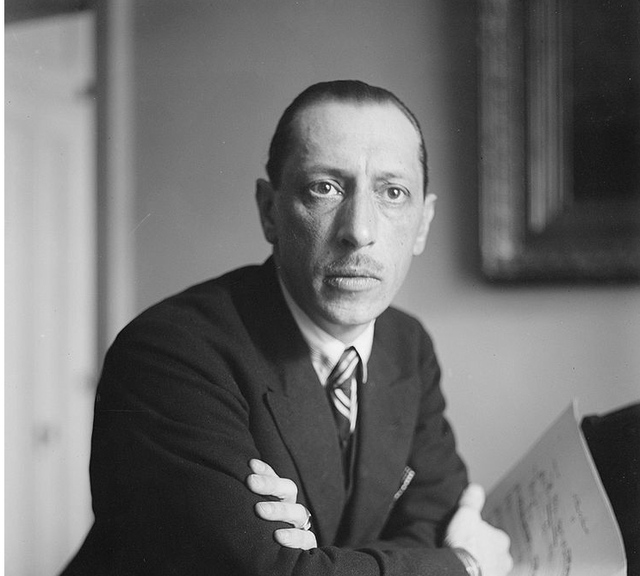

| Arundo donax (future bassoon cane) growing in southern France |