It is significant that Shostakovich Symphony No.10 was finished a few months after Stalin's death. Shostakovich had been kept on a short leash by the Stalin administration. Thus, he supported his family by writing film scores and patriotic music, but secretly, he worked on his own music, holding it back until he felt more safe. Stalin died March 5, 1953; Symphony No.10 was finished October 25, 1953.

Shostakovich had been asked to provide program notes for Symphony No. 10, but he refused, saying only that he had wished "to portray human emotions and passions." The world was left to speculate on his intentions without any hints from the composer. A listener might observe that most of the symphony is rather dark, somber, troubling, mysterious. Then out of the blue, the finale (the last part of the 4th movement) is suddenly upbeat and conventional. Was this an ironic bow towards Soviet authority? When asked about that, Shostakovich replied, "Let them guess."

The bassoon solos fall into the somber, anguished category (except for the final solo in the extreme low range which is almost annoyingly happy). Shostakovich is famous among bassoonists for writing some of the lengthiest bassoon solos in the orchestral literature, such as this one in the first movement:

The above pictured bassoon part to Shostakovich 10 belongs to the Columbus Symphony's Artistic Advisor, Gunther Herbig, who is conducting us in Shostakovish 10 this week, so the breath marks are his. Maestro Herbig asked the accompanying instruments (2nd bassoon and contrabassoon) to play at a true

piannisimo so that the first couple of phrases of the solo could be played in rather hushed tones without being obliterated by the accompaniment.

My teacher, K. David Van Hoesen used to speak often about the manner in which a bassoonist moves his/her fingers. For a legato solo like the one above, he would have advised moving the fingers "as if you're molding clay." Jerky, nervous finger movement is not at all likely to produce a smooth legato phrase.

Sometimes, though, I go too far with the clay molding concept, and my fingers become lazy, not moving simultaneously. That is also unacceptable. I spent a good deal of time just smoothly transitioning from note to note in the phrase above, making sure that the connections from one note to the next were just right- accurate but still smooth.

Vibrato is important in this solo, and I like to think of it increasing as the volume increases. I recently heard a recording of a famous Broadway singer, Patti LuPone, singing

Don't Wait for Me, Argentina,

and her vibrato was beautifully crystal clear and varied. Her vibrato is easy to imitate because it is so clear, so I used her example in preparing this solo.

The last phrase of the above solo, beginning with the eight notes in 6 after 31, is challenging to pace. Should that crescendo go all the way from the beginning of the phrase to the final G flat3? Wow- that would be quite an accomplishment on an instrument like the bassoon with such a limited dynamic range. Somehow, I don't think that's what Shostakovich intended. I think the crescendo should lead to the B flat3 at 3 before 32, and the volume should be maintained until backing off slightly before the final hairpin at 32. Part of the reason for this is that the notes in the high range need to be strong to project.

I spent a lot of time matching the timbre of the notes in the last line of the solo. To really hear what's going on, I recorded myself. To me, matching tone quality from note to note is one of the main challenges of bassoon playing. Tone quality matching varies from bassoon to bassoon, but no bassoon is perfect that way. It is always necessary to tweak, mainly using the air stream and sometimes using alternate fingerings.

The above solo requires the bassoonist to really go all out in the last phrase. When coaching solos like this one, Mr. Van Hoesen was known to say," If your face isn't turning red, then you're not playing it correctly!"

The 3rd movement is easy compared to the lyrical solos in this symphony. (It's not a "turn red in the face" solo!) My main goal is to play it in an extremely rhythmic fashion:

Maestro Herbig has crossed out the decrescendo in 4 and 5 before 112. I suspect it has something to do with projection. I always try to follow the instructions of the composer, but the conductor is the authoritative interpreter of the composer's intentions.

The 4th movement opens with lonely, anguished woodwind cries, first from the oboe, then flute, then bassoon:

It's very important to exaggerate the dynamics. (Mr. Van Hoesen constantly reminded his students of this. The bassoon is such an understated instrument that we really have to overdo everything in order to get our intentions across to the audience.) While preparing this solo, I taped myself quite a few times. I heard on the tape that my forte B flat4 four measures before 150 sounded not quite strong enough to be the peak of this powerful solo. I experimented with fingerings and found that the note took on the perfect character if I added both the Dflat and Eflat keys with the 4th finger left hand. I have never used that fingering before- I just made it up. It makes the B flat very strong- just right for that phrase. The diminuendo does not begin until the quadruplets- on most recordings the bassoonist has already dropped the volume on the Eflat3 after the Bflat4, which is way too soon. By the way, this is another "red in the face" moment for the bassoonist- to me, it feels as though my eyes are popping out of my head. For that reason, I try not to over-practice the peaks of the phrases, preferring to save my eye popping for the concerts.

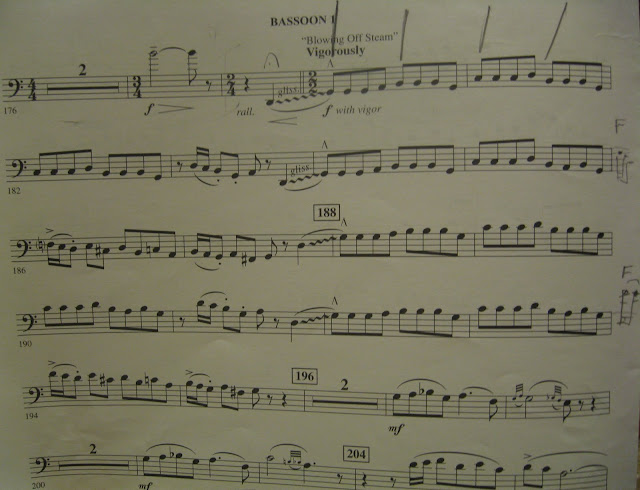

The final solo occurs in the all too-happy finale later in the 4th movement:

For this, I use a very strong sounding low reed- the type I'd use for Peter and the Wolf rather than the softer sounding type I'd use for the opening of Tchaikowsky Symphony. No. 6. I prefer not to switch reeds during a performance, but in this case it makes sense since I need a reed favoring the high range for the other solos, and this low solo simply sounds better on a low reed. I practiced the above solo with a metronome- the tempo is a rather fast 176 to the quarter, so it doesn't hurt to check for rhythmic accuracy.

We have just finished rehearsing, and now the weather has taken a turn for the worst. We have 6 inches on the ground and it's still coming down....I hope that tonight's and tomorrow night's concerts go on as planned!