Ravel composed the music for the ballet Daphnis et Chloe as a commission for Sergei Diaghilev. It was premiered in Paris by Ballet Russe in 1912. Many musicians consider this to be Ravel's orchestral masterpiece - its huge orchestra, (optional) chorus and lush, passionate melodies have made it a favorite of audiences worldwide. Ravel extracted music from the hour-long ballet score to create two suites, the second (and more popular) of which includes the rousing "Danse generale".

| Maurice Ravel in 1914 |

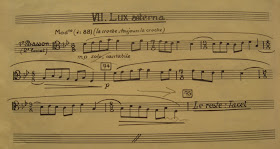

Daphnis is famous for its woodwind parts, especially the flute solos. Although the bassoons are not particularly prominent in the piece, our parts are notoriously difficult, if unheard. In fact, many bassoonists consider the Daphnis bassoon parts to be unplayable. (No doubt, some orchestral bassoon parts truly are unplayable!) If asked my opinion, I suppose I'd say that it is unlikely that any bassoonist would be able to execute each passage in Daphnis with 100% perfection at a reasonably fast tempo. However, near-perfection is possible, and it's worth putting in the time to attempt to nail it reasonably well.

One thing I've noticed recently about practicing difficult technical passages is that it's helpful to keep track of progress. I've developed a habit of penciling in my achieved metronome marking at the end of each practice session. I mark it right in the music so that it will be visible each time I practice it.

It's extremely heartening to discover that with each practice session, the achieved tempo increases. Frankly, I was surprised to see the evidence of progress - before I began keeping track, I often had the impression that I was just spinning my wheels. Now I'm able to see actual proof of progress. (If not, then it's time to re-assess one's practice techniques!)

I always start with the tempo at which I can play the passage accurately, which, due to the difficulty of the passage in question, is always very slow. I do not allow myself to increase the metronome speed until I can play the passage perfectly several times in succession at the current tempo. During each practice session, I begin at a tempo which is slower than my last highest tempo, to give my fingers and brain the benefit of slower-than-necessary review.

|

| The most difficult section of the Ravel Daphnis 1st bassoon part! |

To me, it's very daunting to play a simple melody such as this one. It has to be perfect. That means the intonation has to be perfect, the sound has to be even, the articulation must be perfect, the slurs must be perfectly smooth regardless of the fingerings involved, and any markings in the part must be observed. Oh, and of course the rhythm must be perfect.

Two of those requirements are easy to practice. Intonation is practiced by setting a drone to a reference pitch (I usually used Bflat for this solo). The drone can be played by certain types of electronic tuners, on a computer using an online pitch-producing tuner, or on an electronic keyboard which can sustain pitches. Then the melody is played against the drone. It's easy to hear any pitch problems. Rhythm is easy to practice as well, with a metronome. Despite the odd meters, I set my metronome to 88 to the quarter. (Since I often practice with the metronome beating on the offbeats, it does not concern me when the metronome switches from beating on the beat to off the beat in this excerpt.) But because I don't like to become locked into any particular tempo, I make sure to sometimes practice it at different tempos, even at times like this when the composer has provided a metronome marking. Live performances are not metronomic, and I like to plan for flexibility.

The other issues (evenness, smoothness, articulation, dynamics, phrasing, tone quality) are best addressed by recording. Although I own a high quality recorder, it's a big hassle to get it out, re-read the directions and figure out how to operate the #&*@% thing each time I want to record. Since I always have my phone with me, I use that. I have recorded thousands of bassoon passages over the past year or so - in fact, I wore out the battery of my last iPhone by recording so much. Of course we always listen to ourselves while we're practicing, but the recorder offers the perspective of the outside observer, which often exposes hitherto hidden flaws.

If I had to decide which was more challenging - the worst fast passage of Daphnis or the simple melody of the Duruflé, I can say without hesitation that the simple melody is the greater challenge to me. How about you?

.

I assume you erase the metronome markings before you return the music, but not everyone does. I found a collection of metronome markings in another Ravel, the passage in the third movement of the piano concerto that you have written about in another post, and nothing is more discouraging than to read the tempo in which someone else could play it ;).

ReplyDeleteC., yes, you're right. I intended (but forgot) to write that I erase the markings once we start rehearsing the piece. No bassoonist wants to see someone else's progress report in the music! However, what you saw in your part to the Ravel may have been the last bassoonist's attempt to use a metronome to figure out the conductor's (and soloist's) tempo so that he/she could practice at that tempo. Still, that should have been erased as well, especially since the tempo of that movement varies so much according to the preferences of the soloist and conductor.

ReplyDeleteBetsy

Fascinating. Though I'm a rank amateur, I really appreciated the detail you covered, from your notations (I would've also written in all of the C-clef notes (pained smile)) to practice tempo and how you addressed all the challenges of a the solo. Recording yourself really is possibly the most enlightening thing, especially if you've never done it before.

ReplyDeleteThanks for all the terrific advice!