This is the program:

Prokofiev - Lieutenant Kije

Borodin - Polovetsian Dances

Tchaikovsky - 1812 Overture

(And there's also an encore which shall remain a secret.)

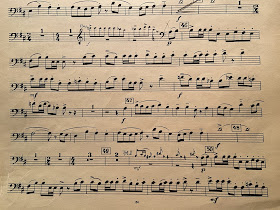

The bassoon is not featured heavily in this program as a solo instrument but there is always plenty to keep us occupied. The details can be daunting.....I noticed that there were 3 intervals which captured much of my attention this week. An interval, in case any non-musicians are reading this, may be defined as the distance between two notes. And one of the main intervals vying for my attention this week is the one which opens the first movement Lt. Kije bassoon solo (played here with a metronome on 80 and a drone on Bb):

Often there is a noise between the high Bb and the F below it, thereby ruining the interval. Smooth playing is one of the great challenges of bassoon playing...left to its own devices, the bassoon sounds pretty rough and rocky. But in the hands of an aware player, many of those rough edges are smoothed out. It takes some work though. To master the interval from high Bb to F, the air and embouchure must be subtly manipulated AND the finger movement from the Bb fingering to the F must be absolutely perfect. We must will the bassoon to cooperate, as thortugh we're reining in a defiant toddler.

In that same solo, sometimes the Bb to the E natural is also a troublesome interval, benefiting from an embouchure shift on the E. And finally, the low D to the low Bb might be awkward. For me it requires a forceful movement of the left thumb. By this point in the solo, the player has surely moved back on the reed, so the main problem here is the swift and strong motion of the left thumb.

I recommend practicing this solo with a metronome. The reason is because this is one of the many solos in which the bassoonist tends to lag behind. Practicing with a metronome prepares the player to keep the tempo moving throughout the solo. I looked at the score to see if there was a tempo marking, and sure enough there was: 80 beats per minute. As always, though, I practiced with the metronome on faster and slower tempos so that I'm prepared for anything.

Many recordings of this piece feature faulty intonation in this bassoon solo. Practicing the solo with a sound drone on Bb will greatly reduce the chances of playing out of tune on the solo in the orchestra. This level of preparation may seem like overkill but I think pays off. It's better to be over-prepared than under-prepared.

There is a tricky technical passage in the second movement of Lt. Kije which presents a different type of interval challenge - one that is solved by the fingers exclusively - between low Eb and low Gb:

All four of the above mentioned intervals benefit from isolated practice (meaning practicing only the interval). I recall many a lesson with K. David Van Hoesen when one interval would be played over and over, with discussion, until it really sounded ultra smooth and connected, with the first note clearly leading to the next. He frequently began lessons by asking to hear a broken arpeggio all slurred, paying very close attention to each interval.

The 4th movement of Lt. Kije features two bassoons and a tenor saxophone in a unison soli beginning a beat before 46:

Good intonation and ensemble are of paramount importance here. The staccatos are ideally crisp, with clear accents, including the accented eighth at the end of each phrase (which may be the opposite of the way we often end phrases!). The sixteenths are best double-tongued because of the tempo and character.

That reminds me of something that happened during this afternoon's rehearsal. Our music director Rossen Milanov summarized with one word what he wanted from the orchestra: character. Similarly, my teacher K. David Van Hoesen used to insist that his students play with character and commitment at all times. That's a valuable goal to have in mind throughout our musical endeavors.

The first time I ever used double tonguing in an orchestra was in the Borodin Polovetsian Dances. At the time I assumed it was difficult because I was a double-tonguing novice, but I have since learned that it's an unusually taxing passage (occurring twice, with different notes):

|

| score pages from Borodin Prince Igor (Polovetsian Dances) with tongued bassoon parts encircled |

The first entrance of the first bassoon in the Lento of Rimsky-Korsakov's Le Coq d'Or Suite presents a different type of demanding detail:

It looks harmless.....it's nothing but a D3 in whole notes, right? Well....the clarinets begin the soft woodwind chord before the 1st bassoon enters, and they are playing very, very, very quietly, as only clarinetists can do. The entering bassoon is sure to sound like a bull in a china shop. I actually considered using my flat pp fingering (which means I'd add the first finger of the right hand) but I decided it was too likely to be flat, ruining the intonation of the chord. So I'm suffering through the entrance with the normal fingering. I try not to drink coffee within 30 minutes of playing a piece like this, because caffeine makes it harder to control delicate entrances such as this one. The second bassoon enters a bar later on the B natural below the D of the 1st bassoon. (I'd much prefer to play the easy-to-control, ultra cooperative B natural!)

In movement III of the Rimsky-Korsakov, the oboe begins an Allegretto solo in 6/8 with the bassoon entering later. The parts are kind of similar; it sounds as though they are supposed to line up better than they do, as though the oboe and bassoon are clumsily and unsuccessfully trying to dance together. The bassoon solo should equal the oboe solo rather than accompany it, while matching the oboe's staccato and general style:

The bassoons certainly can't be heard well in the above passages, but it's incumbent on us to do our best to master our entire program including loud tuttis.

Even Tchaikovsky's bombastic 1812 Overture has some details to fret over. On the first page there is an exposed passage (beginning in measure 45 with the cellos) which is a technical entanglement in the triplets in measures 47 and 51:

In measure 47 above I use the most basic fingering for Eb (just the 1st and 3rd fingers of the left hand plus the whisper key). With most reeds, that fingering is in tune on my bassoon although I suspect that fingering may not be useful on all bassoons. I use that same Eb fingering again in measure 51. It's a little bit disconcerting the use that fingering, since it's not one that we commonly use, and it can be unstable. It's hard to trust the fingering, but it is technically preferable.

As you can see, I wrote in the first note of the next line (Eb) at the end of measure 51 above. Such visual aids seem to help in difficult technical passages. (No use making a mistake because we don't know what the next note is!)

These are just a few of the daunting details of the first bassoon parts for this weekend's Columbus Symphony concerts. If you're in the central Ohio area, you can hear it live on Friday and Saturday night at 7:30pm or Friday morning at 10am. Hope to see you there!