Last night the Columbus Symphony performed with The Chieftains

It was a thoroughly enjoyable concert; there's a reason why The Chieftains are world famous! I kept thinking of my grandmother throughout the concert. Although her ancestors originated from France, she was born and raised in Ireland. I remember watching the Boston Pops on TV with my grandmother when I was a child, and of course, being located in Boston, they played a lot of Irish tunes. Every time they did, my grandmother would order me to get up and "dance the jig," which I did, to the best of my untrained ability.

Even though the symphony only played during half of the concert, I can report that once again, my theory was proved. No matter what concert or repertoire we're playing, there's always at least one "issue" to be concerned about. We bassoonists are nearly never off the hook completely!

One of the pieces we performed last night was Suite from Far and Away by John Williams.

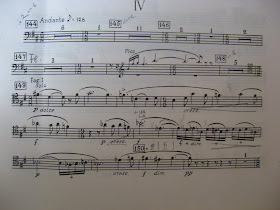

The entire piece is full of technical challenges, with the bassoon often participating in heavily ornamented melodies. But there's one passage in particular which requires us to be very much on the ball:

The bassoons are exposed at the 2/2 marked "Vigorously." It's in a fast 2, and I clearly marked the slash marks on the beat so there'd be no uncertainty. It goes by really quickly, and for me it was absolutely necessary to pencil in the first few notes of the next lines at the ends of the 2nd and 4th lines above. I think that any little trick which increases the likelihood of the successful execution of our assigned parts is worth the effort.

Sunday, February 28, 2010

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

"Romance of the Cello" Columbus Symphony audio stream

Romance of the Cello

IV - Allegro giocoso (9:32)

| Adams: The Chairman Dances |

Composer: John Adams

Conductor: Edwin Outwater

Venue: Ohio Theatre (Columbus)

Recording Date: Sun 21 Feb 2010

| Lalo: Concerto for Cello in D minor |

Composer: Edouard Lalo

Artist: Amit Peled (Cello)

Conductor: Edwin Outwater

Venue: Ohio Theatre (Columbus)

Recording Date: Sun 21 Feb 2010

| I - Prelude: Lento - Allegro maestoso (13:40) |

| II - Intemezzo: Andantino con moto - Allegro presto (6:18) |

| III - Introduction: Andante - Allegro vivace (7:58) |

| Prokofiev: Symphony no 5 in B flat major, Op. 100 |

Composer: Sergei Prokofiev

Conductor: Edwin Outwater

Venue: Ohio Theatre (Columbus)

Recording Date: Sun 21 Feb 2010

| I - Andante (12:44) |

| II - Allegro marcato (8:46) |

| III - Adagio (11:44) |

Monday, February 22, 2010

More French orchestra streaming videos

I have encountered more two orchestral videos featuring French bassoons. First, Musique francaises:

Musiques francaises

The program includes such bassoon rich selections as the Chabrier España and the Dukas The Sorcerer's Apprentice.

Au programme :

- Emmanuel Chabrier : España, poème symphonique

- Edouard Lalo : Symphonie Espagnole pour violon et orchestre

- Camille Saint-Saëns : Concerto pour violoncelle et orchestre

- Paul Dukas : L'apprenti Sorcier, poème symphonique

- Camille Saint-Saëns : Danse Bacchanale, extrait de Samson et Dalila

Next, l'Orchestre de Paris under the direction of Christoph Eschenbach, who is also piano soloist in 2 Mozart piano Concerti:

l'Orchestre de Paris

Au programme :

- Concerto pour piano n° 12 en la majeur, K 414

- Concerto pour piano n° 23 en la majeur, K 488

The principal bassoonist (playing German bassoon) in this video is extremely animated! I wonder why l'Orchestre de Paris uses German bassoons.........

Musiques francaises

The program includes such bassoon rich selections as the Chabrier España and the Dukas The Sorcerer's Apprentice.

Au programme :

- Emmanuel Chabrier : España, poème symphonique

- Edouard Lalo : Symphonie Espagnole pour violon et orchestre

- Camille Saint-Saëns : Concerto pour violoncelle et orchestre

- Paul Dukas : L'apprenti Sorcier, poème symphonique

- Camille Saint-Saëns : Danse Bacchanale, extrait de Samson et Dalila

Next, l'Orchestre de Paris under the direction of Christoph Eschenbach, who is also piano soloist in 2 Mozart piano Concerti:

l'Orchestre de Paris

Au programme :

- Concerto pour piano n° 12 en la majeur, K 414

- Concerto pour piano n° 23 en la majeur, K 488

The principal bassoonist (playing German bassoon) in this video is extremely animated! I wonder why l'Orchestre de Paris uses German bassoons.........

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Adams, Lalo and Prokofiev

The most difficult piece of music I've ever played was the John Adams Chamber Symphony, which was the last Adams piece the Columbus Symphony performed. This week we're performing another piece by Adams, The Chairman Dances, Foxtrot for Orchestra, which is infinitely more playable than the Chamber Symphony. In fact, it's hard to believe that the same man wrote both bassoon parts.

The main challenge in The Chairman Dances is concentrating enough to keep one's place during continuously repeated phrases. The rhythm becomes more complicated in certain sections, and the music is rental, so it has markings from other players. Those markings sometimes interfere, as demonstrated below:

With so many pencil markings, most of which make no sense, it's difficult to read the part. I tried to alter it as best I could with an eraser, but my success was limited. Whenever I mark the beats in a part which is rhythmically tricky, I try to make my markings extremely neat and precise. I know that I tend to be visually oriented to the extreme, but I believe that neat, precise pencil markings are more likely to result in accurate rhythm for any player, even those who are not as visual.

The Lalo Cello Concerto features a rather unusual bassoon solo, which repeats 4 times, in the 3rd movement:

It's 6/8 meter, with 2 beats per measure. Most bassoonists would have the option of either single or double tonguing the 16ths which first occur 3 after B. I planned to double tongue, but since it recurred so many times, I was afforded the luxury of experimenting in rehearsal with single tonguing also. It's one of those solos with I think benefits from the sense of velocity created by double tonguing, and I chose to double tongue. I like it when I have the opportunity to experiment during rehearsals to choose the type of tonguing which best fits the orchestral context (and tempo). Sometimes it's difficult to plan in advance.

Prokofiev Symphony No. 5 opens with a soli for flute and bassoon in octaves:

This passage benefits from strong breath support to ensure smoothness. I use the image of blowing up a balloon to assist with that. It's easy to become distracted with worry about playing each note in tune and with a sound which matches the other notes, and the overall smoothness of the passage can suffer from that. It's always important to think in terms of the entire phrase rather than getting caught up on individual notes. The time to address individual notes is at home during preparation, not onstage during rehearsals or performances.

It's best to breath whenever the principal flutist breathes. In my case, that means breathing only once, in the 5th measure after the D. Of course we try to make the breath as quick as possible so as to lessen the likelihood of interfering with the flow.

I try to do everything I can to ensure the best possible musical outcome. For example, I'm fussy about the placement of my music stand. I've already written about my belief that the stand has to be far enough away from the bassoon that the sound is not distorted from ricocheting off the stand. I've also written about the importance of having the visual aspect of the music just so. Check out the following, which is the ending of the above excerpt:

I tried an interesting experiment with the passage at 55 in the 2nd movement:

The fingerings are a bit tricky, especially at a quick tempo. Thursday morning before rehearsal, I wanted to practice that passage but didn't have time to get the bassoon out. I took the bus to rehearsal that day, and I tried to mentally practice that passage on the bus. I heard the notes in my head while imagining that I was fingering the notes on the bassoon. I'm pleased to report that it seemed to me that my mental practice turned out to be as effective as actual practice would have been. This trick will undoubtedly come in handy again before long!

The main challenge in The Chairman Dances is concentrating enough to keep one's place during continuously repeated phrases. The rhythm becomes more complicated in certain sections, and the music is rental, so it has markings from other players. Those markings sometimes interfere, as demonstrated below:

With so many pencil markings, most of which make no sense, it's difficult to read the part. I tried to alter it as best I could with an eraser, but my success was limited. Whenever I mark the beats in a part which is rhythmically tricky, I try to make my markings extremely neat and precise. I know that I tend to be visually oriented to the extreme, but I believe that neat, precise pencil markings are more likely to result in accurate rhythm for any player, even those who are not as visual.

The Lalo Cello Concerto features a rather unusual bassoon solo, which repeats 4 times, in the 3rd movement:

It's 6/8 meter, with 2 beats per measure. Most bassoonists would have the option of either single or double tonguing the 16ths which first occur 3 after B. I planned to double tongue, but since it recurred so many times, I was afforded the luxury of experimenting in rehearsal with single tonguing also. It's one of those solos with I think benefits from the sense of velocity created by double tonguing, and I chose to double tongue. I like it when I have the opportunity to experiment during rehearsals to choose the type of tonguing which best fits the orchestral context (and tempo). Sometimes it's difficult to plan in advance.

Prokofiev Symphony No. 5 opens with a soli for flute and bassoon in octaves:

This passage benefits from strong breath support to ensure smoothness. I use the image of blowing up a balloon to assist with that. It's easy to become distracted with worry about playing each note in tune and with a sound which matches the other notes, and the overall smoothness of the passage can suffer from that. It's always important to think in terms of the entire phrase rather than getting caught up on individual notes. The time to address individual notes is at home during preparation, not onstage during rehearsals or performances.

It's best to breath whenever the principal flutist breathes. In my case, that means breathing only once, in the 5th measure after the D. Of course we try to make the breath as quick as possible so as to lessen the likelihood of interfering with the flow.

I try to do everything I can to ensure the best possible musical outcome. For example, I'm fussy about the placement of my music stand. I've already written about my belief that the stand has to be far enough away from the bassoon that the sound is not distorted from ricocheting off the stand. I've also written about the importance of having the visual aspect of the music just so. Check out the following, which is the ending of the above excerpt:

It bothers me to no end that the A3 and F3 are placed at the same height! For my taste, the F has to be a certain distance below the A in order for my brain to be able to easily interpret the music. I have to plan for the worst possible circumstances, when I might be exhausted or distracted. So I penciled in an "A" below the A3 and an "F" below the F3, just in case my brain is not functioning optimally. Sometimes I resort to rewriting the part; in fact, I seem to recall that I rewrote a page or two of the above-mentioned Adams Chamber Symphony because the previous bassoonist had marked it up so copiously............. .

I tried an interesting experiment with the passage at 55 in the 2nd movement:

The fingerings are a bit tricky, especially at a quick tempo. Thursday morning before rehearsal, I wanted to practice that passage but didn't have time to get the bassoon out. I took the bus to rehearsal that day, and I tried to mentally practice that passage on the bus. I heard the notes in my head while imagining that I was fingering the notes on the bassoon. I'm pleased to report that it seemed to me that my mental practice turned out to be as effective as actual practice would have been. This trick will undoubtedly come in handy again before long!

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

Carl Nielsen: Serenata-Invano

Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) is Denmark's best-known composer. Rumor has it that he had a lifelong fascination with the wind instruments, and one of his signature compositions is his Quintet, Op. 43 for woodwinds and horn. His most mature works are his 6 symphonies, which feature very carefully written wind and brass passages designed to challenge the players and to show off the unique characteristics of each instrument.

He wrote the Serenata-Invano in 1914 when double bassist Anton Hegner asked him to write something light to add to a concert on which he and some colleagues from the Danish Royal Orchestra were performing the Beethoven Septet for clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin, viola, cello and bass. Thus, Nielsen's "Serenade in Vain" was scored for Beethoven's winds (clarinet, bassoon and horn) plus cello and bass.

At that time in history, there was apparently a revived interest in the serenade genre originated by Mozart. Dvorak, Brahms, Elgar, Strauss and Tchaikowsky had indulged in serenade writing shortly before Nielsen wrote Serenata-Invano. All of these Romantic era composers, including Nielsen, borrowed Mozart's model of form and mood for their serenades.

Serenata-Invano consists of 3 continuous movements: Allegro, Adagio, and a concluding March. Nielsen himself provided these program notes:

Serenata-Invano is unfamiliar to me, and frankly, I hadn't paid much attention to Nielsen and his works until now. My research on Nielsen disclosed his brooding over his career. He wrote this in his local newspaper in 1925:

It's worth the effort though, because those slurs need to be practiced anyway!

Here's a recording of the piece, although I don't know who the bassoonist is:

Nielsen Serenata-Invano

He wrote the Serenata-Invano in 1914 when double bassist Anton Hegner asked him to write something light to add to a concert on which he and some colleagues from the Danish Royal Orchestra were performing the Beethoven Septet for clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin, viola, cello and bass. Thus, Nielsen's "Serenade in Vain" was scored for Beethoven's winds (clarinet, bassoon and horn) plus cello and bass.

At that time in history, there was apparently a revived interest in the serenade genre originated by Mozart. Dvorak, Brahms, Elgar, Strauss and Tchaikowsky had indulged in serenade writing shortly before Nielsen wrote Serenata-Invano. All of these Romantic era composers, including Nielsen, borrowed Mozart's model of form and mood for their serenades.

Serenata-Invano consists of 3 continuous movements: Allegro, Adagio, and a concluding March. Nielsen himself provided these program notes:

“Serenata-Invano is a humorous trifle. First the gentlemen play in a somewhat chivalrous and showy manner to lure the fair one out onto the balcony, but she does not appear. Then they play a slightly languorous strain (Poco adagio), but that doesn’t have any effect either. Since they have played in vain (in vano), they don’t care a straw, and shuffle off home to the strains of the little final march, which they play for their own amusement.”I am studying Serenata-Invano for a performance with some Columbus Symphony colleagues in elementary schools in a couple of weeks. These days, symphony jobs often include chamber music performances, especially in the realm of education and audience development. Symphony fans of any age enjoy the opportunity to see and hear musicians in smaller settings.

Serenata-Invano is unfamiliar to me, and frankly, I hadn't paid much attention to Nielsen and his works until now. My research on Nielsen disclosed his brooding over his career. He wrote this in his local newspaper in 1925:

“If I could live my life again, I would chase any thoughts of Art out of my head and be apprenticed to a merchant or pursue some other useful trade the results of which could be visible in the end.... What use is it to me that the whole world acknowledges me, but hurries away and leaves me alone with my wares until everything breaks down and I discover to my disgrace that I have lived as a foolish dreamer and believed that the more I worked and exerted myself in my art, the better position I would achieve. No, it is no enviable fate to be an artist. We are dependent upon the most capricious fluctuations in the public’s taste, and even if their taste is sympathetic to us ... what difference does it make? We hear applause and shouts of bravo, but that almost makes matters worse. And our publishers - well, they would rather see the back of us.”The piece is charming, but the bassoon part is awkward, aptly demonstrating Nielsen's desire to challenge the bassoonist. Take a look at the slurred triplet passages:

It's worth the effort though, because those slurs need to be practiced anyway!

Here's a recording of the piece, although I don't know who the bassoonist is:

Nielsen Serenata-Invano

Columbus Symphony Shostakovich 10 now streaming online

Here's the link to last Friday night's Shostakovich 10 performance. I have also pasted it onto the sidebar of this blog, since it's such a bassoon-rich piece. Gunther Herbig was the conductor.

Sunday, February 7, 2010

le basson français

I have been fascinated by the French basson for a long time. In the hands of masters such as Maurice Allard, Paul Hogne, Julien Hardy and Gilbert Audin, it is a hauntingly beautiful instrument, noted for its smooth, singing, lyrical capabilities. Yet the French basson can also perform acrobatics unthinkable on the much more common German bassoon.

I often search YouTube for examples of French basson playing, but I am invariably disappointed. Why has the classical music world all but abandoned this unique and intriguing instrument?

Imagine my delight when I happened upon this video streamed all-Ravel concert today:

streaming video of Philharmonique de Radio France

The bassoons in the video are indeed French bassons, even though German bassoons are becoming increasingly common even in French orchestras.

Vivent longtemps le basson français !

I often search YouTube for examples of French basson playing, but I am invariably disappointed. Why has the classical music world all but abandoned this unique and intriguing instrument?

Imagine my delight when I happened upon this video streamed all-Ravel concert today:

streaming video of Philharmonique de Radio France

The bassoons in the video are indeed French bassons, even though German bassoons are becoming increasingly common even in French orchestras.

Vivent longtemps le basson français !

Friday, February 5, 2010

Shostakovich 10

It is significant that Shostakovich Symphony No.10 was finished a few months after Stalin's death. Shostakovich had been kept on a short leash by the Stalin administration. Thus, he supported his family by writing film scores and patriotic music, but secretly, he worked on his own music, holding it back until he felt more safe. Stalin died March 5, 1953; Symphony No.10 was finished October 25, 1953.

Shostakovich had been asked to provide program notes for Symphony No. 10, but he refused, saying only that he had wished "to portray human emotions and passions." The world was left to speculate on his intentions without any hints from the composer. A listener might observe that most of the symphony is rather dark, somber, troubling, mysterious. Then out of the blue, the finale (the last part of the 4th movement) is suddenly upbeat and conventional. Was this an ironic bow towards Soviet authority? When asked about that, Shostakovich replied, "Let them guess."

The bassoon solos fall into the somber, anguished category (except for the final solo in the extreme low range which is almost annoyingly happy). Shostakovich is famous among bassoonists for writing some of the lengthiest bassoon solos in the orchestral literature, such as this one in the first movement:

The above pictured bassoon part to Shostakovich 10 belongs to the Columbus Symphony's Artistic Advisor, Gunther Herbig, who is conducting us in Shostakovish 10 this week, so the breath marks are his. Maestro Herbig asked the accompanying instruments (2nd bassoon and contrabassoon) to play at a true piannisimo so that the first couple of phrases of the solo could be played in rather hushed tones without being obliterated by the accompaniment.

My teacher, K. David Van Hoesen used to speak often about the manner in which a bassoonist moves his/her fingers. For a legato solo like the one above, he would have advised moving the fingers "as if you're molding clay." Jerky, nervous finger movement is not at all likely to produce a smooth legato phrase.

Sometimes, though, I go too far with the clay molding concept, and my fingers become lazy, not moving simultaneously. That is also unacceptable. I spent a good deal of time just smoothly transitioning from note to note in the phrase above, making sure that the connections from one note to the next were just right- accurate but still smooth.

Vibrato is important in this solo, and I like to think of it increasing as the volume increases. I recently heard a recording of a famous Broadway singer, Patti LuPone, singing Don't Wait for Me, Argentina, and her vibrato was beautifully crystal clear and varied. Her vibrato is easy to imitate because it is so clear, so I used her example in preparing this solo.

The last phrase of the above solo, beginning with the eight notes in 6 after 31, is challenging to pace. Should that crescendo go all the way from the beginning of the phrase to the final G flat3? Wow- that would be quite an accomplishment on an instrument like the bassoon with such a limited dynamic range. Somehow, I don't think that's what Shostakovich intended. I think the crescendo should lead to the B flat3 at 3 before 32, and the volume should be maintained until backing off slightly before the final hairpin at 32. Part of the reason for this is that the notes in the high range need to be strong to project.

I spent a lot of time matching the timbre of the notes in the last line of the solo. To really hear what's going on, I recorded myself. To me, matching tone quality from note to note is one of the main challenges of bassoon playing. Tone quality matching varies from bassoon to bassoon, but no bassoon is perfect that way. It is always necessary to tweak, mainly using the air stream and sometimes using alternate fingerings.

The above solo requires the bassoonist to really go all out in the last phrase. When coaching solos like this one, Mr. Van Hoesen was known to say," If your face isn't turning red, then you're not playing it correctly!"

The 3rd movement is easy compared to the lyrical solos in this symphony. (It's not a "turn red in the face" solo!) My main goal is to play it in an extremely rhythmic fashion:

Maestro Herbig has crossed out the decrescendo in 4 and 5 before 112. I suspect it has something to do with projection. I always try to follow the instructions of the composer, but the conductor is the authoritative interpreter of the composer's intentions.

The 4th movement opens with lonely, anguished woodwind cries, first from the oboe, then flute, then bassoon:

It's very important to exaggerate the dynamics. (Mr. Van Hoesen constantly reminded his students of this. The bassoon is such an understated instrument that we really have to overdo everything in order to get our intentions across to the audience.) While preparing this solo, I taped myself quite a few times. I heard on the tape that my forte B flat4 four measures before 150 sounded not quite strong enough to be the peak of this powerful solo. I experimented with fingerings and found that the note took on the perfect character if I added both the Dflat and Eflat keys with the 4th finger left hand. I have never used that fingering before- I just made it up. It makes the B flat very strong- just right for that phrase. The diminuendo does not begin until the quadruplets- on most recordings the bassoonist has already dropped the volume on the Eflat3 after the Bflat4, which is way too soon. By the way, this is another "red in the face" moment for the bassoonist- to me, it feels as though my eyes are popping out of my head. For that reason, I try not to over-practice the peaks of the phrases, preferring to save my eye popping for the concerts.

The final solo occurs in the all too-happy finale later in the 4th movement:

For this, I use a very strong sounding low reed- the type I'd use for Peter and the Wolf rather than the softer sounding type I'd use for the opening of Tchaikowsky Symphony. No. 6. I prefer not to switch reeds during a performance, but in this case it makes sense since I need a reed favoring the high range for the other solos, and this low solo simply sounds better on a low reed. I practiced the above solo with a metronome- the tempo is a rather fast 176 to the quarter, so it doesn't hurt to check for rhythmic accuracy.

We have just finished rehearsing, and now the weather has taken a turn for the worst. We have 6 inches on the ground and it's still coming down....I hope that tonight's and tomorrow night's concerts go on as planned!

Shostakovich had been asked to provide program notes for Symphony No. 10, but he refused, saying only that he had wished "to portray human emotions and passions." The world was left to speculate on his intentions without any hints from the composer. A listener might observe that most of the symphony is rather dark, somber, troubling, mysterious. Then out of the blue, the finale (the last part of the 4th movement) is suddenly upbeat and conventional. Was this an ironic bow towards Soviet authority? When asked about that, Shostakovich replied, "Let them guess."

The bassoon solos fall into the somber, anguished category (except for the final solo in the extreme low range which is almost annoyingly happy). Shostakovich is famous among bassoonists for writing some of the lengthiest bassoon solos in the orchestral literature, such as this one in the first movement:

The above pictured bassoon part to Shostakovich 10 belongs to the Columbus Symphony's Artistic Advisor, Gunther Herbig, who is conducting us in Shostakovish 10 this week, so the breath marks are his. Maestro Herbig asked the accompanying instruments (2nd bassoon and contrabassoon) to play at a true piannisimo so that the first couple of phrases of the solo could be played in rather hushed tones without being obliterated by the accompaniment.

My teacher, K. David Van Hoesen used to speak often about the manner in which a bassoonist moves his/her fingers. For a legato solo like the one above, he would have advised moving the fingers "as if you're molding clay." Jerky, nervous finger movement is not at all likely to produce a smooth legato phrase.

Sometimes, though, I go too far with the clay molding concept, and my fingers become lazy, not moving simultaneously. That is also unacceptable. I spent a good deal of time just smoothly transitioning from note to note in the phrase above, making sure that the connections from one note to the next were just right- accurate but still smooth.

Vibrato is important in this solo, and I like to think of it increasing as the volume increases. I recently heard a recording of a famous Broadway singer, Patti LuPone, singing Don't Wait for Me, Argentina, and her vibrato was beautifully crystal clear and varied. Her vibrato is easy to imitate because it is so clear, so I used her example in preparing this solo.

The last phrase of the above solo, beginning with the eight notes in 6 after 31, is challenging to pace. Should that crescendo go all the way from the beginning of the phrase to the final G flat3? Wow- that would be quite an accomplishment on an instrument like the bassoon with such a limited dynamic range. Somehow, I don't think that's what Shostakovich intended. I think the crescendo should lead to the B flat3 at 3 before 32, and the volume should be maintained until backing off slightly before the final hairpin at 32. Part of the reason for this is that the notes in the high range need to be strong to project.

I spent a lot of time matching the timbre of the notes in the last line of the solo. To really hear what's going on, I recorded myself. To me, matching tone quality from note to note is one of the main challenges of bassoon playing. Tone quality matching varies from bassoon to bassoon, but no bassoon is perfect that way. It is always necessary to tweak, mainly using the air stream and sometimes using alternate fingerings.

The above solo requires the bassoonist to really go all out in the last phrase. When coaching solos like this one, Mr. Van Hoesen was known to say," If your face isn't turning red, then you're not playing it correctly!"

The 3rd movement is easy compared to the lyrical solos in this symphony. (It's not a "turn red in the face" solo!) My main goal is to play it in an extremely rhythmic fashion:

Maestro Herbig has crossed out the decrescendo in 4 and 5 before 112. I suspect it has something to do with projection. I always try to follow the instructions of the composer, but the conductor is the authoritative interpreter of the composer's intentions.

The 4th movement opens with lonely, anguished woodwind cries, first from the oboe, then flute, then bassoon:

It's very important to exaggerate the dynamics. (Mr. Van Hoesen constantly reminded his students of this. The bassoon is such an understated instrument that we really have to overdo everything in order to get our intentions across to the audience.) While preparing this solo, I taped myself quite a few times. I heard on the tape that my forte B flat4 four measures before 150 sounded not quite strong enough to be the peak of this powerful solo. I experimented with fingerings and found that the note took on the perfect character if I added both the Dflat and Eflat keys with the 4th finger left hand. I have never used that fingering before- I just made it up. It makes the B flat very strong- just right for that phrase. The diminuendo does not begin until the quadruplets- on most recordings the bassoonist has already dropped the volume on the Eflat3 after the Bflat4, which is way too soon. By the way, this is another "red in the face" moment for the bassoonist- to me, it feels as though my eyes are popping out of my head. For that reason, I try not to over-practice the peaks of the phrases, preferring to save my eye popping for the concerts.

The final solo occurs in the all too-happy finale later in the 4th movement:

For this, I use a very strong sounding low reed- the type I'd use for Peter and the Wolf rather than the softer sounding type I'd use for the opening of Tchaikowsky Symphony. No. 6. I prefer not to switch reeds during a performance, but in this case it makes sense since I need a reed favoring the high range for the other solos, and this low solo simply sounds better on a low reed. I practiced the above solo with a metronome- the tempo is a rather fast 176 to the quarter, so it doesn't hurt to check for rhythmic accuracy.

We have just finished rehearsing, and now the weather has taken a turn for the worst. We have 6 inches on the ground and it's still coming down....I hope that tonight's and tomorrow night's concerts go on as planned!